Investors significantly underestimate the collateral damage from COVID-19

April 8, 2020

Jean-Pierre Couture

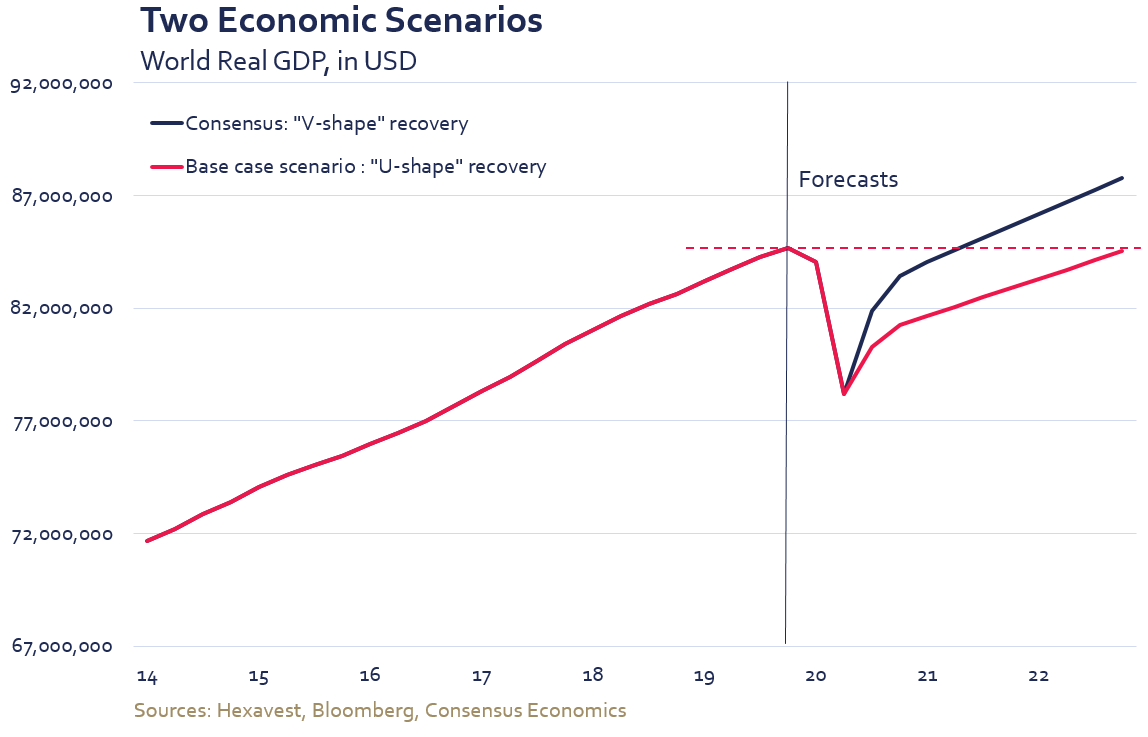

The COVID-19 crisis has obliged us to revise our macroeconomic vector sharply downward. Our recent analysis suggests that there are two likely economic scenarios that could play out in the years to come:

- The first scenario – also the current consensus – calls for a very deep, but short, global recession, followed by a strong V-shaped recovery later this year. The rebound would come with a return to normality after the COVID-19 crisis, helped by the unprecedented stimulus measures announced by governments and central banks.

- The second scenario is more worrisome: a deep global recession which will be exacerbated by the high levels of corporate debt in the U.S., Europe and China. In this scenario, the downturn will be prolonged by a cascade of defaults, bankruptcies and permanent job losses.

As we have advanced in our analysis of global economic conditions, we have become increasingly convinced that the second scenario is more likely. Here are the reasons why we are concerned about a longer recession.

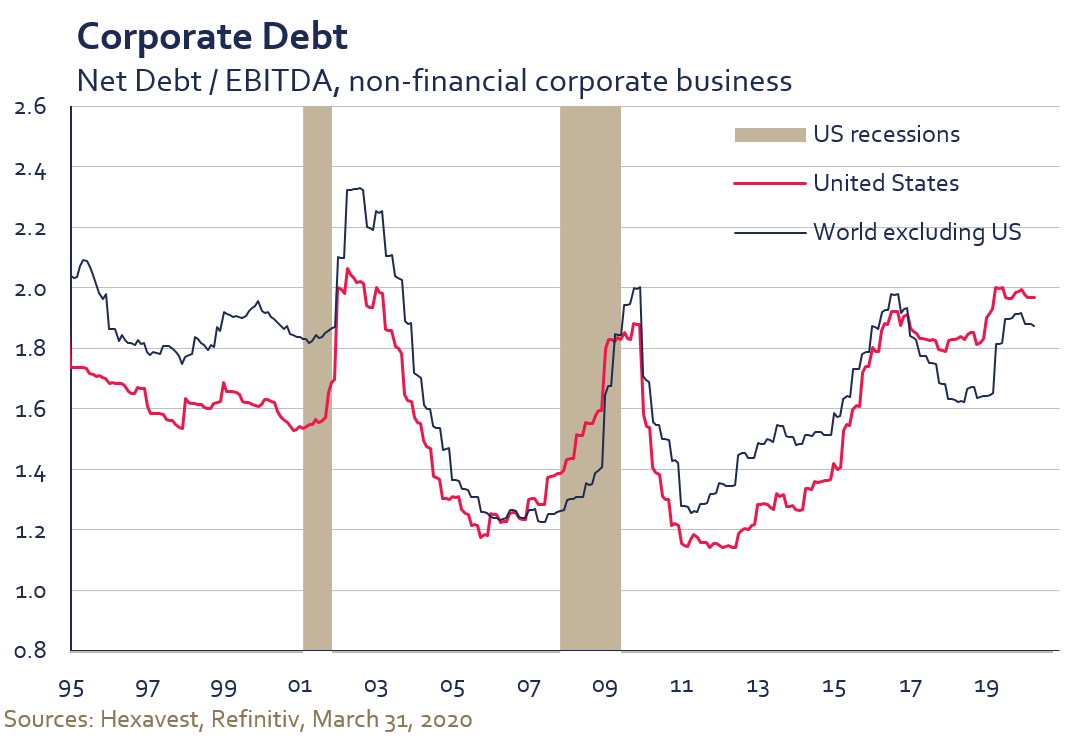

An already fragile macrofinancial context

In recent years, we have expressed concern about the pronounced acceleration of corporate debt levels. Our reasoning is simple: more indebted companies are more sensitive to the vagaries of the financial markets and more vulnerable to economic slowdowns. An increase in defaults, bankruptcies and layoffs could drag the economy down even further and keep it stuck in recession for longer. Finally, the proportion of companies rated BBB, only one notch above junk bonds, is worrying. A wave of downgrades could lead to contagion in the financial markets (Ford, Macy’s and Kraft Heinz were recently downgraded for example). The risks created by excessive debt were well documented in 2019, notably by the IMF, the OECD, the ECB and the U.S. Federal Reserve.1

How did we get to this point?

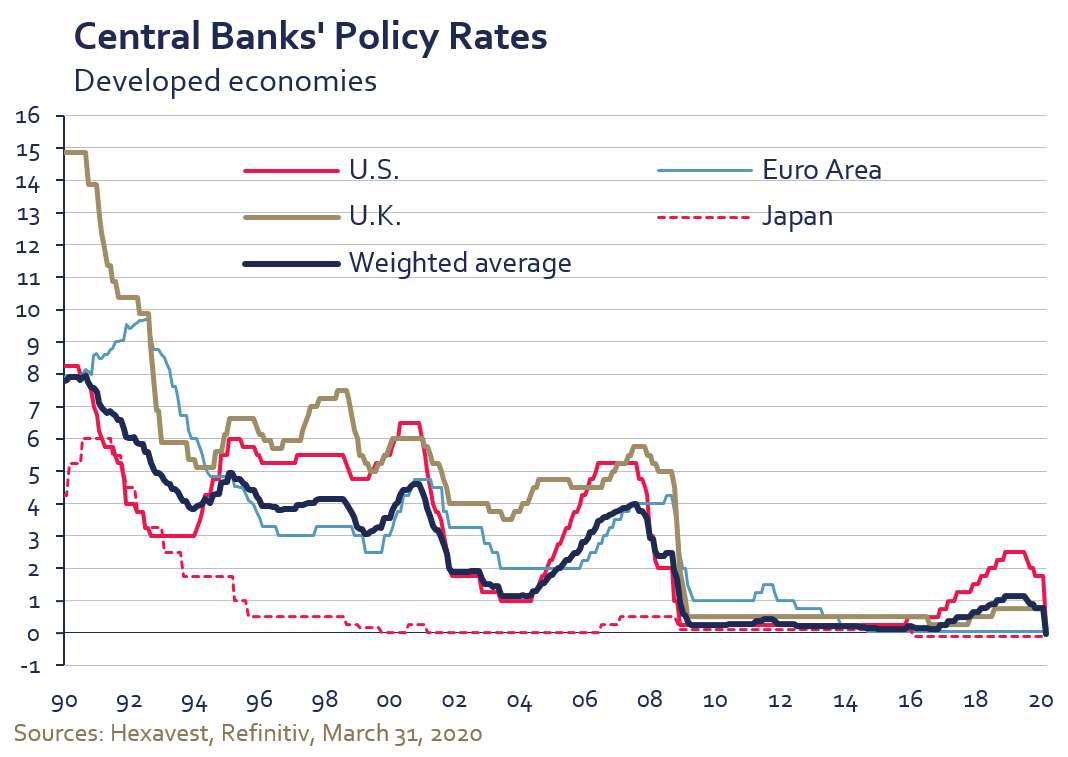

In previous economic downturns, central banks were able to smooth out growth by significantly lowering their key interest rates to support a recovery. Rates in the developed countries were cut by almost 4% on average over the past three cycles.

Each time, the central banks borrowed from future growth to get the economy back on track. Over time, this successive easing of credit conditions contributed to an increase in household and business debt. The excessive debt loads of U.S. households led to the 2008 financial crisis. Today, it is excessive corporate debt that poses a major macrofinancial problem.

Despite the lessons offered by the financial crisis, central banks continued to boost credit by keeping their key interest rates very low over the past decade, in addition to intervening in the bond market by lowering long-term yields. As a result, investors seeking yields higher than those of sovereign bonds were obliged to buy riskier assets, including stocks and corporate bonds.

“While easier financial conditions have supported economic growth and helped contain downside risks to the outlook in the near term, they have also encouraged more financial risk-taking and a further buildup of financial vulnerabilities, putting medium-term growth at risk.... Policymakers urgently need to take action to tackle financial vulnerabilities that could exacerbate the next economic downturn.”

- Global Financial Stability Report, IMF, October 2019

Even when economic growth and full employment returned, central bankers failed to normalize interest rates. In 2018, when the unemployment rate reached an all-time low in the OECD countries, the major central banks tried to raise their key interest rates and stop their bond purchases. But corporate debt was so excessive and the bond refinancings in the pipeline were so massive2 that the global outlook deteriorated rapidly when interest rates were raised. The central banks had to back down at the end of 2018 by lowering their key rates again. Having gone much too far, the major central banks were unable to normalize the situation.

The COVID-19 crisis struck in this context of great financial vulnerability.

Crisis triggers a succession of problems

The COVID-19 crisis is having an immediate and unprecedented macroeconomic impact. Stopping activity and locking down billions of people around the world have no precedent in recent history. Given the scale of this phenomenon, as well as its duration, we are concerned about the possibility of a succession of crises. Indeed, the COVID-19 crisis may expose many weak links.

1. Humanitarian cost

First, the crisis has a humanitarian cost. The pandemic calls for a strong, swift, coordinated response from the authorities to protect populations. But this approach hasn’t been taken everywhere. Some countries have been slow to recognize the crisis, to respond to it and to impose restrictions. Others, such as Brazil, have opted for denial or have decided they can’t afford to shut down their economies. The latter will be the case in a number of emerging countries with poor populations. They may regard COVID-19’s human toll as the lesser evil. The outcome will probably be a longer crisis, a delayed return to normality and a greater humanitarian cost.

2. Social and economic costs

Second, the crisis entails significant socioeconomic costs. Millions of households have seen their incomes fall suddenly as a result of job losses or disappear altogether with the closure of family businesses. These households will have difficulty meeting their financial obligations, such as rent, mortgage payments, credit card bills, health care expenses, etc. The decline of the financial markets also hurts savers and retirees and undermines their purchasing power. After the crisis, it will take some time for households to recover their standard of living, their confidence and their spending habits.

As for corporations, we are concerned that earnings will plunge amid a cascade of defaults and bankruptcies. Companies are likely to postpone investment, development and hiring projects until their profitability, or even survival, is ensured. Before the crisis, some estimated3 that one-sixth of U.S. companies were so-called zombies, namely companies that struggle to pay interest on their debt and depend on refinancing at very low interest rates to survive. In today’s environment, where earnings have plummeted and investors’ appetite for debt refinancing has diminished, the proportion of troubled firms has exploded.

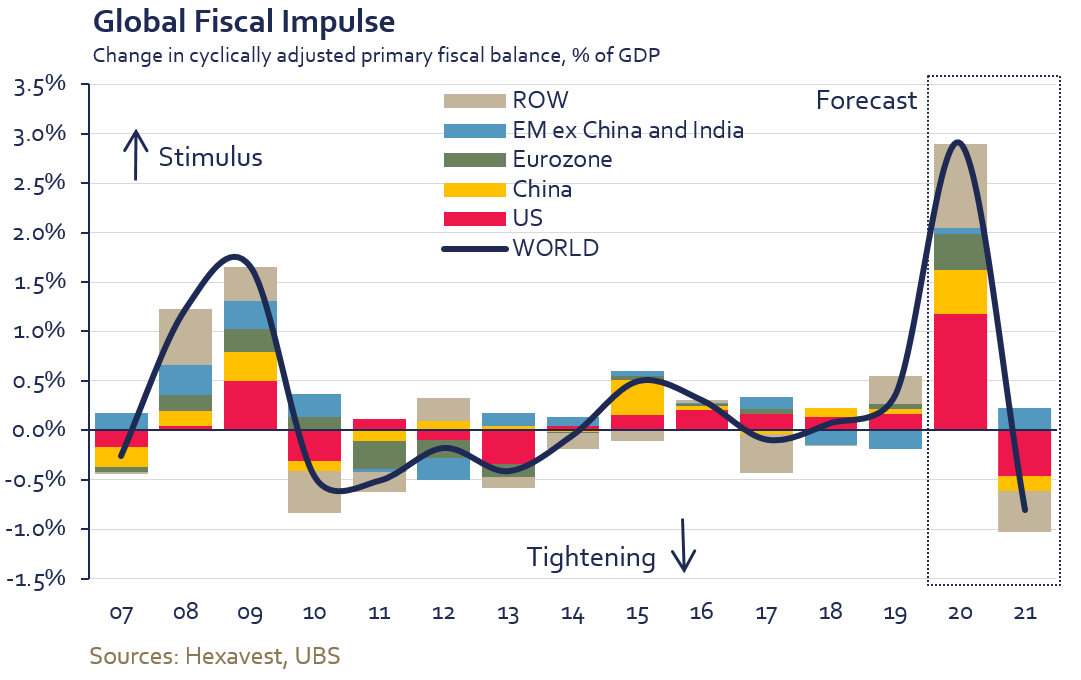

The strong and rapid response by governments and central banks to support households and businesses will no doubt enable us to avoid the worst. But, in our view, the announced measures, however ambitious they may be, will not offset the negative economic impacts, nor will they bring about the V-shaped recovery hoped for by the consensus.

3. Risk of a public finance crisis

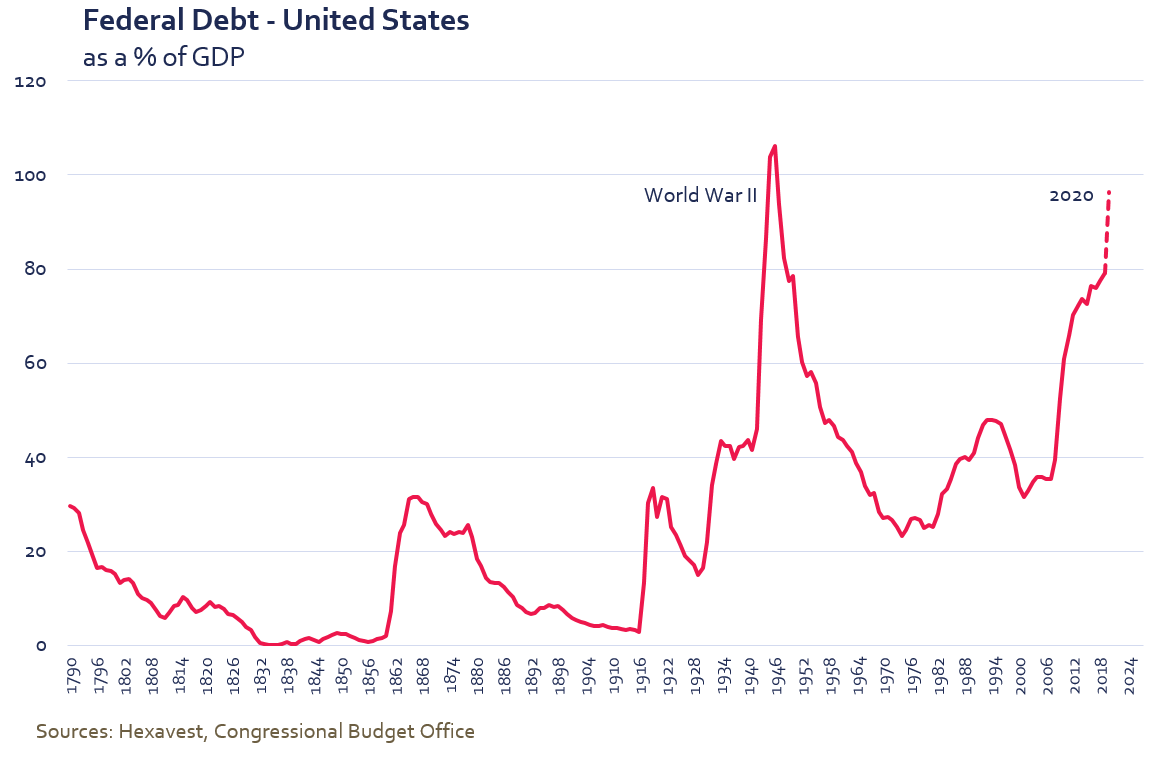

Finally, the third aspect is a public finance crisis. A number of countries have put in place strong measures to cushion the shock. The announced emergency measures, as well as the magnitude of the current shock, far exceed what was seen during the 2008 financial crisis.

The essential measures taken to tide households over until the end of the crisis are costly and will cause the public debt to balloon, as will the bailouts of businesses deemed strategic for the economy.

What will remain after the initial economic shock abates and the virus is under control? Governments that are more indebted and more vulnerable than ever. It is difficult to foresee a scenario in which the state of public finances will not limit the ability to take action when a future shock occurs or will not dampen economic growth for several years, because governments will have to raise taxes and reduce their expenses.

Like Europe’s 2010-11 sovereign debt crisis, which occurred in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the current crisis could shake the perception of debt sustainability in some countries. It could even boost Euroskepticism in the years to come. In this context, we expect significant and sustained measures by central banks.

The role of central banks: avoid a financial crisis

Central banks will play a dominant role in the current crisis. Even though they cannot stop the recession in the short term, they will undoubtedly do everything in their power to prevent a financial crisis from making the situation worse. In addition to lowering their key interest rates aggressively, a number of central banks have announced measures such as various asset-purchase programs, advantageous financing for banks, relaxation of banks’ capital and reserve requirements, and massive injections of liquidity into the money markets. They will try to reduce the long-term economic damage4 caused by the COVID-19 crisis by acting as the lender of last resort to companies that are indebted but viable over the long term.

That being said, a post-mortem will be in order once the crisis is contained. Will governments want to let companies become indebted to the point of creating systemic risk? Will share buybacks be limited or even prohibited? What will happen to the dividends paid out by rescued firms? Are central banks comfortable maintaining the moral hazard associated with their actions? What are the other long-term consequences of expanding central bank balance sheets? On this point, we know that monetization is no miracle solution, Japan being a prime example.

Hexavest’s mission: avoid traps and preserve capital

We therefore think the V-shaped-recovery scenario expected by the consensus is becoming less likely. In our view, it will take far longer than a few quarters for consumers, businesses and governments to recover from the COVID-19 crisis, given the cascade of economic and financial events it will trigger.

At the end of the first quarter of 2020, however, optimism was trying to make a comeback on the stock market, with the MSCI World Index up more than 15% from its lows. In our view, volatility’s return to the financial markets will not be short-lived. Of course, there will be periods of optimism, especially when promising COVID-19 treatments are announced, but there will also be periods of macroeconomic and financial disappointment.

In this context of acute uncertainty, we prefer a cautious approach. We think that the managers who focus on avoiding mistakes will be those who emerge as winners. Much of Hexavest’s record of success is due to our knack for avoiding traps. We are confident that this will enable us to distinguish ourselves in this unprecedented environment.

[1] Global Financial Stability Report: Lower for Longer, IMF, October 2019; Financial Stability Report, U.S. Federal Reserve, May 2019; Corporate Bond Markets in a Time of Unconventional Monetary Policy, OECD, February 2019.

[2] A total of $4 trillion over three years (2020-2022) according to the OECD: Corporate Bond Markets in a Time of Unconventional Monetary Policy, OECD, February 2019.

[3] Mentionned by Rushi Sharma in the article “Will the coronavirus trigger a corporate debt crisis?” published by Financial Times on March 15, 2020.

[4] Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen. The Federal Reserve must reduce long-term damage from coronavirus, Financial Times, March 18, 2020.

Source of all data and information: Hexavest as at March 31, 2020, unless otherwise specified.

This material is presented for informational and illustrative purposes only. It is meant to provide an example of Hexavest’s investment management capabilities and should not be construed as investment advice or as a recommendation to purchase or sell securities or to adopt any particular investment strategy. Any investment views and market opinions expressed are subject to change at any time without notice. This document should not be construed or used as a solicitation or offering of units of any fund or other security in any jurisdiction.

The opinions expressed in this document represent the current, good-faith views of Hexavest at the time of publication and are provided for limited purposes, are not definitive investment advice, and should not be relied on as such. The information presented herein has been developed internally and/or obtained from sources believed to be reliable; however, Hexavest does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of such information. Predictions, opinions, and other information contained herein are subject to change continually and without notice and may no longer be true after the date indicated. Hexavest disclaims responsibility for updating such views, analyses or other information. Different views may be expressed based on different investment styles, objectives, opinions or philosophies. It should not be assumed that any investments in securities, companies, countries, sectors or markets described were or will be profitable. It should not be assumed that any investor will have an investment experience similar to any portfolio characteristics or returns shown. This material may contain statements that are not historical facts (i.e., forward-looking statements). Any forward-looking statements speak only as of the date they are made, and Hexavest assumes no duty to and does not undertake to update forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements are subject to numerous assumptions, risks, and uncertainties, which change over time. Future results may differ significantly from those stated in forward-looking statements, depending on factors such as changes in securities or financial markets or general economic conditions. Not all of Hexavest’s recommendations have been or will be profitable.

This material is for the benefit of persons whom Hexavest reasonably believes it is permitted to communicate to and should not be reproduced, distributed or forwarded to any other person without the written consent of Hexavest. It is not addressed to any other person and may not be used by them for any purpose whatsoever. It expresses no views as to the suitability of the investments described herein to the individual circumstances of any recipient or otherwise.